Time may be running out for New Zealand's most sacred tree

Tāne Mahuta (Lord of the Forest) is about 2,500 years old. But its days will be numbered if it succumbs to kauri dieback

New Zealand’s oldest and most sacred tree stands 60 metres from death, as a fungal disease known as kauri dieback spreads unabated across the country.

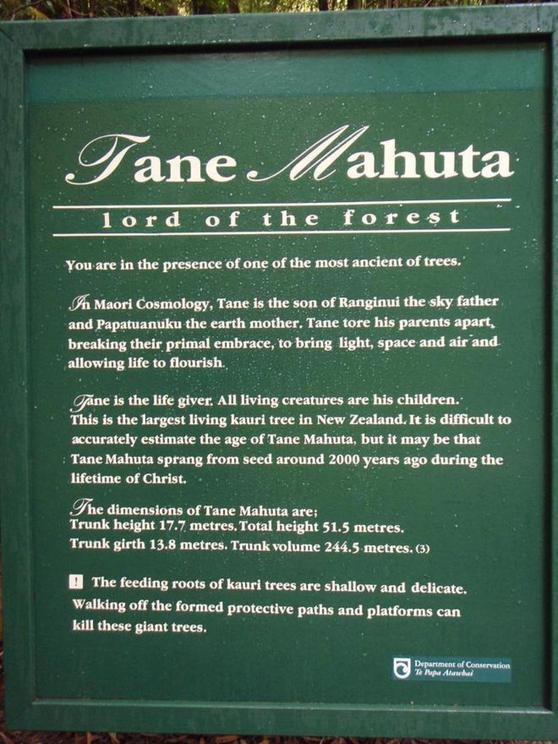

Tāne Mahuta (Lord of the Forest) is a giant kauri tree located in the Waipoua forest in the north of the country, and is sacred to the Māori people, who regard it as a living ancestor.

A blessing ceremony held for Tāne Mahuta in the Waipoua forest of Northland, New Zealand. Photograph: Denise Batchelor

The tree is believed to be around 2,500 years old, and is 13.77m across and more than 50m tall.

Thousands of locals and tourists alike visit the tree every year to pay their respects, and take selfies beside the trunk.

everherenow.com

everherenow.com

Now, the survival of what is believed to be New Zealand’s oldest living tree is threatened by kauri dieback, with kauri trees a mere 60m from Tāne Mahuta confirmed to be infected.

Kauri dieback causes most infected trees to die, and is threatening to completely wipe out New Zealand’s most treasured native tree species, prized for its beauty, strength and use in boats, carvings and buildings.

A kauri tree infected with kauri dieback. Photograph: Denise Batchelor

Despite stringent efforts by local iwi [Māori tribes] to combat the spread – most commonly through infected soil tramped in on walkers’ boots, or the hooves of wild pigs – there is no cure, and native tree experts are calling for international help to slow the demise of kauri dieback and save Tāne Mahuta.

Amanda Black from the Bioprotection Research Centre at NZ’s Lincoln University, estimates Tāne has only three to six months before becoming infected – if he is not already – as his mammoth root system spreads in excess of 60m underground.

An advisory panel was launched by the government in June in a bid to tackle the spread of the disease, but Black says the panel was the equivalent of “shuffling deck chairs on the Titanic.” She wants Tāne soil tested immediately to confirm whether or not the tree is infected, but this option is proving controversial.

On Thursday, Black was invited to attend a hikoi for Tāne in Waipoua forest, held by the local tribe, Te Roroa, who prayed for the tree’s safety and wellbeing as the disease inches ever close.

“We don’t have any time to do the usual scientific trials anymore, we just have to start responding immediately in any way possible; it is not ideal but we have kind of run out of time,” Black says, adding that although there is no cure for kauri dieback there is a range of measures which could slow its progress.

“Tāne is the nearest thing to a sentient being that we can measure time by. For Māori in particular, it is their ancestor. For them to lose trees like that is equivalent to losing family members,” she says.

Taoho Patuawa, a spokesperson for Te Roroa, says solutions being discussed include closing the entire forest and felling nearby infected trees.

Presently, raised boardwalks and boot-cleaning stations are the frontline defence, as well as conservation department rangers, Māori guardians and volunteers who patrol vulnerable forests.

Last year Auckland tribe Te Kawerau a Maki issued a rāhui (temporary ban) over the Waitākere and Hunua ranges to the west of Auckland, prohibiting anyone from entering the forest.

Auckland council added its support and surveillance to the ban this June, but biosecurity experts say locals feel “entitled” to enter the bush, and are largely to blame for ignoring warnings and bans.

“Closure is the best thing we’ve got, especially if the authorities got behind it and enforced it. The forest needs to rest,” says Black.

Conservation minister Eugenie Sage said Kauri dieback was “devastating” for New Zealand’s unique flora and fauna, but said the department of conservation [DOC] was confident the risk of the disease spreading by human traffic was “very low”, and wild pigs were now in the crosshairs.

Dead Kauri trees take on a ghostly white appearance in the landscape, and according to Northland residents, dead Kauri trees are now visible from all the roads surrounding the Waipoua Forest.

“Sometimes people are overwhelmed and end up crying,” Vanessa Rapira of the Te Roroa tribe told the Guardian last year.

For full references please use source link below.