Investigation: Clorox selling pool salt made from fracking wastewater

Clorox Pool Salt packaging used by Eureka Resources at their fracking wastewater treatment plant in Wysox, Pa. © Public Herald

You might be shocked to learn that a Clorox product used to treat swimming pools came from fracking wastewater.

Public Herald has discovered that Eureka Resources, a company based in Pennsylvania, has been treating wastewater from shale gas development — a.k.a. “fracking” — and packaging the crystal byproduct as “Clorox Pool Salt” for distribution since 2017.

The way it works is fracking wastewater gets trucked to Eureka Resources where it’s treated and turned into salt. From there, workers at the facility package the salt into Clorox bags and pallet them for shipment.

While Eureka uses Clorox packaging, and trades in Clorox products, they never deal directly with Clorox. The bags are palleted for an unnamed third-party distributor to be sold to regional stores like Wal-Mart, Home Depot, and Lowes.

Eureka Resources stands by their product safety, citing its own four-step patented treatment system that involves pretreatment, distillation, crystallization and dewasting. The company has operated since 2008 in Pennsylvania, currently with two treatment facilities: one in Williamsport and the Standing Stone Facility in Wysox who produces the pool salt.

Eureka states the Standing Stone facility is “capable of producing clean distilled water, concentrated brine, dry sodium chloride (NaCl) salt and approximately 30% calcium chloride (CaCl)” out of water that contained carcinogens, trade-secret chemicals, heavy metals, and high levels of radioactive material.

Eureka Resources Standing Stone Facility in Wysox, Pa.

Eureka Resources Standing Stone Facility in Wysox, Pa.

Starting in 2015, before it was possible for Eureka to use the salt byproduct for pools, they sold over 4,000 tons of feedstock to Cargill.

The solids leftover after wastewater treatment, often referred to as sludge, are hauled to area landfills that can accept radioactive waste.

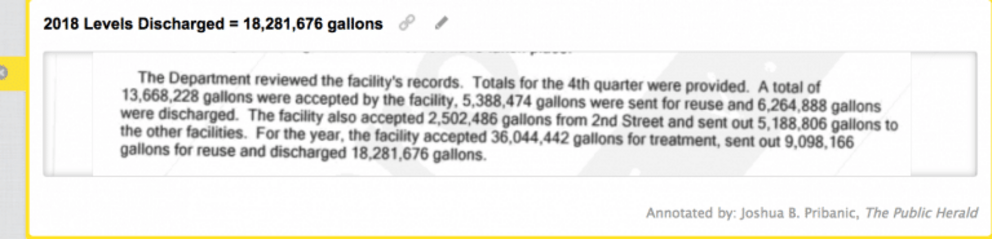

Once the wastewater is treated the state no longer recognizes the remaining water as waste. It can then be discharged into a waterway with an NPDES permit from the EPA. According to Eureka’s 2018 records at Standing Stone, the company discharged 18,281,676 million gallons into the Susquehanna River watershed, for 36,044,422 treated gallons of wastewater.

After treatment, Eureka’s salt is still considered a residual waste by the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection’s (PADEP) WMGR123 permit to operate a waste facility. In 2016, after a “torturous process,” DEP granted Eureka special permission through this permit to package the salt for commercial use. Across Pennsylvania, DEP manages 71 WMGR123 permits, as of spring 2018, with 34 of them active in some form.

Jerel Bogdan, Vice President of Engineering at Eureka Resources, in an interview with Public Herald, stated Eureka’s patented system is “the only one in Pennsylvania that has proven and demonstrated to the DEP that our technology can generate dewasted water. To our knowledge there is no one else in North America who’s able to do that with oil and gas brines.”

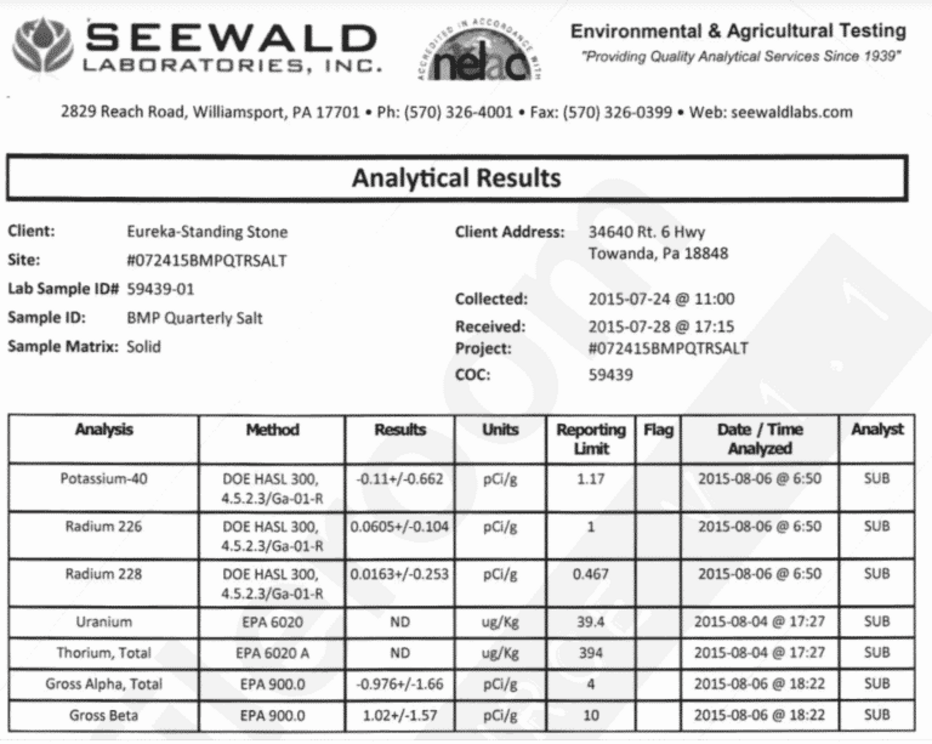

The state’s exclusive agreement with Eureka ensures the salt is screened four times a year for radioactivity. Those quarterly tests have detected radioactive compounds in the salt at levels below background conditions. (There’s no screening daily or for each new shipment.)

The radioactive material in fracking wastewater, such as radium-226, can be 1000 times or greater than what’s considered safe for drinking water. But discussion about fracking and radioactivity rarely makes the national press. A recent article in the Washington Post covering New Mexico’s idea to make fracking wastewater useable for agriculture failed to even mention a potential for radioactive constituents.

A fracking wastewater storage pond in Pennsylvania Gamelands.

A fracking wastewater storage pond in Pennsylvania Gamelands.

Given this knowledge, the Clorox pool salt packaging is not labeled to inform a consumer [e.g. WARNING: this salt is a byproduct of fracking wastewater and handled in a facility that processes radioactive waste.]

That concerns Dr. Daniel Bain, a research professor at University of Pittsburgh’s Department of Geology and Environmental Science who studies radioactivity. “I’d want to see some screening being done to know if Technically Enhanced Naturally Occurring Radioactive Material (TENORM) is being detected,” Bain told Public Herald. TENORM is used to describe enhanced radioactivity coming from fracking wastewater. TENORM is created when naturally occurring radioactive material (NORM) is released and concentrated by human activity, as is the case for wastewater produced by hydraulically fracturing shale deposits for oil and gas.

“I would assume the TENORM would be taken out of the salt,” said Bain, who doesn’t expect the Clorox product to exceed radioactive limits. “But all it takes is a little glitch in the process and you can have a dirty salt at some point,” i.e. salt with TENORM.

Bogdan says any “glitch” is closely monitored and fixed to prevent dirty salt from getting on the market.

When asked whether he would be agreeable to labeling the product, Bogden responded “I would have no problem if that disclosure was asked of us. I don’t entirely disagree with that…If I didn’t have a set of data that is as bullet-proof as possible I would think differently.

“When our salt is analyzed…our salt is indistinguishable from any other commercially saleable sources of salt,” Bogdan added.

Clorox hasn’t returned a request for comment. Their 2018 shareholder report on corporate responsibility fails to mention “product safety” or how the company oversees the source material for its products. (Clorox is listed to have earned $6.1 billion in revenue for 2018.)

Pennsylvania is the second largest natural gas producing state in the United States, which is the largest producer of natural gas in the world. The “Smoking Gun” report series digs deep to expose specific stories of DEP conduct. Is your energy coming from the shale fields of Pennsylvania