Roman army camp found in Netherlands, beyond the empire's frontier

Archaeology students excavate the site of Hoog Buurlo in the Netherlands, where they found a Roman-era military fort.

Archaeologists and students in the Netherlands have unearthed a 1,800-year-old temporary Roman military fort in the Netherlands.

The remains of an ancient Roman army camp have been discovered in the Netherlands, beyond the empire's northern frontier, after researchers used a computer model to pinpoint its location.

The "rare" find, at a site called Hoog Buurlo, shows that Roman forces were venturing beyond the Lower German Limes, the boundary that ran along the Rhine roughly 15.5 miles (25 kilometers) south of the camp.

"For the Netherlands this is only the fourth Roman temporary camp, so quite a rare find," said Saskia Stevens, an associate professor of ancient history and classical civilization at Utrecht University and the principal investigator of the "Constructing the Limes" project that found the fort. "The fact that it was discovered north of the Lower Germanic Limes, beyond the border of the empire, tells us that the Romans did not perceive the Limes as the end of their Empire," Stevens told Live Science in an email.

The fort was likely a temporary marching camp, which troops used for only a few days or weeks, according to a statement from Utrecht University. It's also possible that the camp was a stopover on the way to another camp about a day's march away.

Finding Roman forts

Constructing the Limes, a project led by Utrecht University, aims to understand how the Roman border functioned and to unearth temporary Roman camps north of the boundary.

As a part of the investigation, Jens Goeree, an archaeology student at Saxion University of Applied Sciences, developed a computer program to help predict the location of temporary Roman camps in Veluwe, a region of nature reserves filled with woodlands, grasslands and lakes. This program was based on probability and used data from elevation maps and lidar (light detection and ranging), a technique in which a machine shoots lasers from an aircraft over a site and measures the reflected waves to map the landscape below.

Excavations at the site revealed a temporary Roman military fort in the Netherlands.

Excavations at the site revealed a temporary Roman military fort in the Netherlands.

"He reconstructed possible routes of the Roman army across the Veluwe area, calculating the number of kilometers an army could travel per day," Stevens said. The program also took into account roads and water availability, and looked for the "typical playing card-shaped camps" that Romans constructed, she said.

The computer program didn't disappoint: It led them to the site in Hoog Buurlo within the Veluwe in 2023.

Visiting on foot

In January 2025, the team visited the site to dig archaeological trenches and confirm that the site actually held an ancient fort, according to a statement.

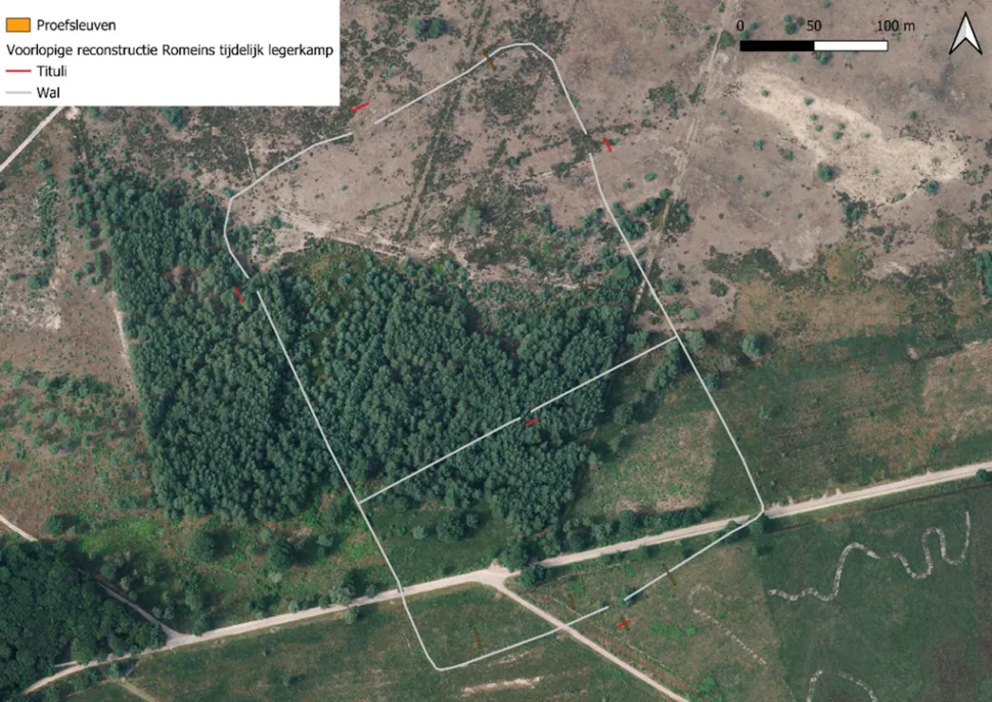

The fort was large — 9 acres (3.6 hectares) — and shaped like a rectangle with rounded corners. It had a V-shaped ditch that was 6.6 feet (2 meters) deep, a 10-foot-wide (3 m) earthen wall, and several entrances, Stevens said. However, the team found only a few artifacts at the site, including a fragment of Roman military armor.

"The limited number of finds is not surprising as the camp was only in use for a short period of time (days, weeks) and the soldiers would have traveled light," Stevens said.

An outline of the newfound fort in the Netherlands. Notice that like many other Roman military forts, it's shaped like a playing card.

An outline of the newfound fort in the Netherlands. Notice that like many other Roman military forts, it's shaped like a playing card.

A lock pin artifact found at the temporary military fort.

A lock pin artifact found at the temporary military fort.

The small number of finds made it hard to date the camp. But by examining the armor and comparing the newfound site to a camp found in 1922 at another site in the Netherlands, the team dated the newly discovered temporary camp to the second century A.D., Stevens said.

The finding shows that the Romans "were clearly active beyond the border and saw that area as their sphere of influence," Stevens said. The region north of the limes was likely an important place to take cattle, hides and even enslaved people.

The people who lived in the area, the Frisii and the Chamavi, already had ties with the Romans. "The Frisians were generally on good terms with the Romans," as they traded with them, Stevens said. Historical sources mention a treaty in which the Frisians paid taxes in the form of cow hides, and they also provided soldiers for the auxiliary troops and members of Nero's (ruled A.D. 54 to 68) imperial bodyguard.