Earthquake struck Machu Picchu in 1450 study concludes

Construction of Machu Picchu was interrupted around 1450 by a powerful earthquake, leaving damage still evident today and prompting the Inca to perfect the seismic-resistant megalithic architecture that is now so famous throughout Cusco, according to a major new scientific study revealed by Peru’s state-run news agency Andina.

The separation of stone blocks at Machu Picchu is due to an earthquake of at least magnitude 6.5 that struck around the year 1450.

The Cusco-Pata Research Project determined that a temblor of at least magnitude 6.5 struck during the reign of the 9th Inca Pachacutec while he was building his now iconic summer estate atop the saddle-ridge between two craggy mountain peaks.

The multidisciplinary research project began in 2016, led by the Geological, Mining and Metallurgical Institute (Ingemmet), with the participation of experts from the United Kingdom, France and Spain.

“What we can see is that there was already construction underway with one type of architecture under Pachacutec,” said the project coordinator Carlos Benavente. “Then, we believe in the middle of that construction of Machu Picchu, there was a major earthquake.”

The earthquake damage is evident in the temple of the Sun, near the Intihuatana, and throughout the ceremonial centers of Machu Picchu.

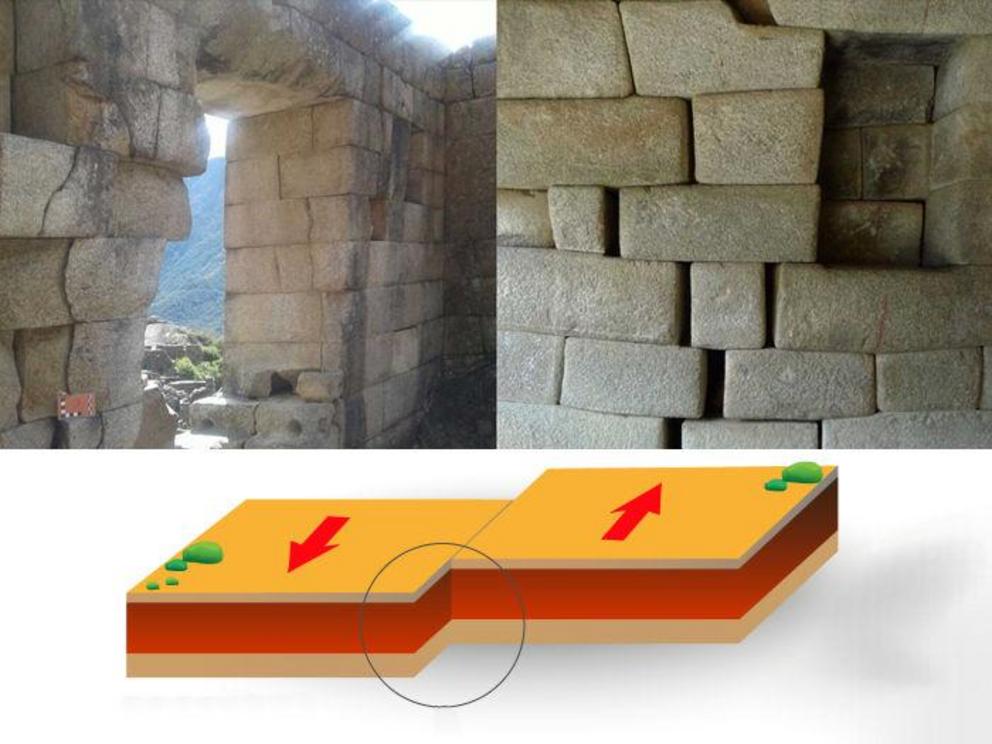

“We see openings between rocks and stones, which is not typical of the Incas because they employed an impeccable, perfect construction. Some edges of the rocks are broken, which means that in the undulation of the earth, they hit each other, which caused the breaks,” Benavente said. “After that, they continued the building in a different manner to complete what would become Machu Picchu.”

Benavente said that “there is no doubt” that the strong earthquake also caused the deformation of the walls of Sacsayhuamán, Tipón and Tambomachay, as well as along the street of the Twelve Angles Stone in the city of Cusco, among other areas.

As a result, the Inca moved away from using smaller stones, assembled in a more rustic cellular architecture, and continued to develop and perfect seismic-resistant trapezoidal structures, with giant stone blocks at the base with narrower upper walls.

“They knew how to coexist with diverse geologic dangers, like earthquakes, landslides and avalanches,” he said.

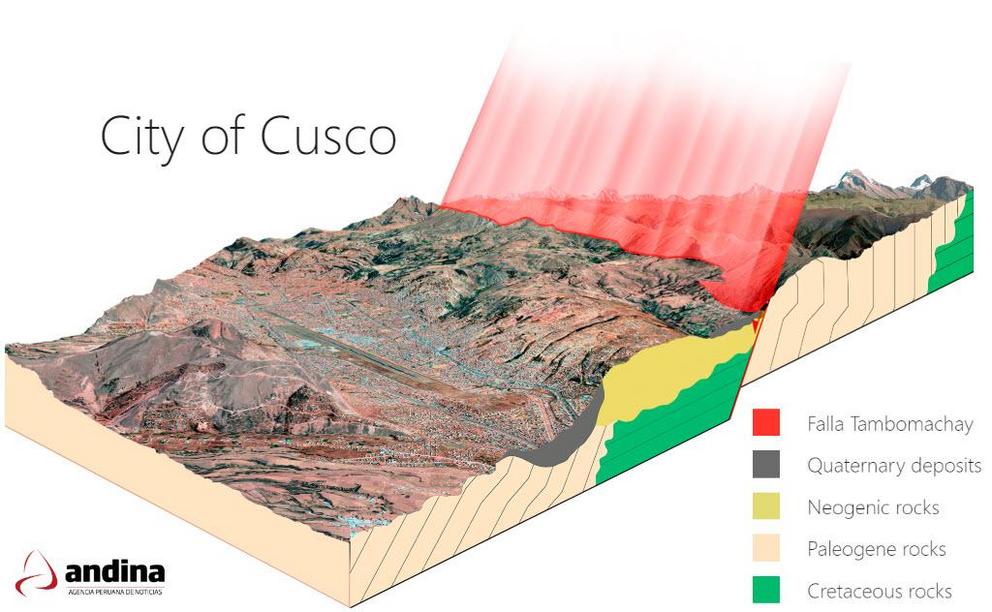

That is why this study is necessary, he added, to help current-day planners analyze the seismic hazards of the Tambomachay and Pachatusan fault lines for the Cusco region.

Not only will this help in the conservation of historic archaeological sites, but also in formulating land management and risk management plans.

“For the first time in history, the techniques of paleoseismology, archaeo-seismology and active tectonics have been combined in a study of this nature,” Benavente said.

The study reveals just how complex the Inca’s understanding of these risk factors was, allowing them to engineer vast terraces on steep and sometimes nearly vertical mountainsides to cultivate crops and manage water resources.

The Inca’s largest expansion occurred on the left bank of the Huatanay River, precisely where the Tambomachay fault is located — begging the question, why build there, despite the risk?

The answer is simple: the geological fissures are an important conduit of water.

“The Incas wanted water; therefore, they preferred to improve the structural conditions of their homes rather than move away from the water resource, Benavente said. The Inca Empire was largely built on understanding and exploiting water resources.

A clear example is Tipón, he said, an engineering marvel of megalithic construction, with aqueducts that have endured numerous earthquakes over the centuries and continue to function to this day.

The Cusco-Pata Research Project is ongoing and is expected to continue well into 2019.